Women in Science: Anna Hughes

Anna Hughes studies ultracool dwarfs - a collection of the smallest, coldest stars in the universe, and substellar objects called brown dwarfs. Very little is known about the radio emission of ultracool dwarfs, as it wasn’t until recently that radio telescopes became powerful enough for us to detect them.

Anna Hughes studies ultracool dwarfs - a collection of the smallest, coldest stars in the universe, and substellar objects called brown dwarfs. Very little is known about the radio emission of ultracool dwarfs, as it wasn’t until recently that radio telescopes became powerful enough for us to detect them.

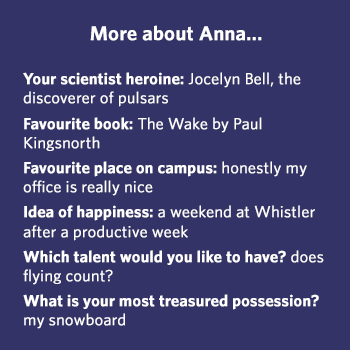

Originally on track to research in philosophy and literature, Anna made the switch to physics after learning about quantum mechanics. She then stumbled upon a project where she searched through the data from the Kepler Space Telescope for planets in orbit around binary star systems – an opportunity that opened her eyes to the excitement of astronomy research. Now, she is an Astrophysics PhD candidate, working on the forefront of technology to unveil the secrets of these mysterious ultracool dwarfs.

We chatted with Anna recently about her path to research, her experience, and the advice she has for future scientists.

How did you become a researcher?

Hughes: My journey here was a bit indirect. When I started college, I was pretty set on studying philosophy and literature while I considered my math and physics courses more of a hobby. Learning about quantum mechanics actually motivated me to switch to focus on physics so I could gain a deeper understanding of the material. During my last year of undergrad I had the opportunity to do some research with data from the Kepler Space Telescope, looking for planets in orbit around binary star systems. While I didn’t find any, I was so excited about actually being able to look at other planetary systems (that might even host life!) that I was totally sold on astronomy research.

Why do you love being a scientist?

Hughes: One of the most exciting things about doing this work specifically is that it’s both new and that there aren’t very many people in my sub-field. We only recently developed radio telescopes sensitive enough to detect ultracool dwarfs at all just because they’re so dim! In my work I feel like I’m really pioneering something - and because it does have implications for planets, it’s easy to get people who aren’t necessarily into astronomy excited about my field.

What are your research questions?

What are your research questions?

Hughes: My biggest research questions are about the smallest, coldest stars in the universe and even smaller objects called brown dwarfs that are somewhere between planets and stars - these are collectively known as ultracool dwarfs. I’m trying to understand how ultracool dwarfs behave at radio frequencies. For a long time it was assumed that they would not have any radio emission whatsoever, so it came as a surprise when astronomers discovered that around 10% of them are active at radio frequencies. I do observations of ultracool dwarfs, in a higher radio frequency range where only a few have even been observed, in order to figure out what physical processes are driving the radio emission. This impacts how the dwarfs’ magnetic fields are configured and on the atmospheres of planets in orbit around ultracool dwarfs. At these high radio frequencies, we can see evidence of violent “space weather” - explosive events from the dwarf that could strip away the ozone from surrounding planets’ atmospheres. I have a new paper on this topic that should be coming out in the next few months!

How can we better address equity, diversity, and inclusion (EDI) in your field?

Hughes: One thing we can do to move forward is to reduce the proportion of responsibility put on women and minorities to solve EDI; instead, we need people already in positions of power to prioritize these efforts.

Women and minorities are disproportionately junior, making them both vulnerable and lacking the institutional power to create meaningful change. Doing so, could mean sacrificing their own careers for the potential future career of another person in a similar scenario.

What are examples of challenges you faced as a women researcher, and what is your advice to aspiring young women researchers?

Hughes: One of the hardest things I’ve struggled with is imposter syndrome; it gets better the further along I go, but it’s always there. It was at its worst when I first started my path in physics. I didn’t yet know what imposter syndrome was but I felt on some level that I wasn’t supposed to be where I was. That feeling was sort of bolstered by some interactions I had with different professors; for example, in undergrad I once had a “research” meeting with a professor who spent the entire time telling me about all his girlfriends, even after I tried repeatedly to redirect the conversation to physics. It was clear to me that while he felt comfortable detailing his romantic life to me, he didn’t take my potential as a physicist seriously.

I think one of the best pieces of advice I can offer upcoming women researchers is to not internalize these kinds of interactions. Bear in mind that while senior researchers in the field may be accomplished, they aren’t omniscient and they aren’t immune to the biases of their time. If they treat you like you are inferior from the get-go, it isn’t because they are seeing into your core as a scientist, it’s because they are reflecting their own prejudices onto you.

What do you want to achieve with your research?

Hughes: My hope is that through my career I’ll be able to build a more complete picture of ultracool dwarfs across many frequencies, and extend the kind of techniques I use to study larger stars as well as planets. This is going to be really important for understanding magnetic field generation in fully convective objects AND determining which stars have the most/least potential for hosting planets with Earth-like life.

***

This article is one of the many stories celebrating International Day of Women and Girls in Science, which takes place every year on February 11. Spearheaded by the United Nations, this day promotes full and equal access to participation in science, technology, and innovation for women and girls. The Faculty of Science is supporting this day by featuring ten inspiring women researchers who are making their mark at UBC and beyond. science.ubc.ca/womeninscience.