Laws of motion before Newton

Jean Buridan, Questions on the Eight Books of Aristotle's Physics

(14th century)

It is sought whether a projectile after leaving the hand of the

projector is moved by the air or by what it is moved. ...This question I judge to

be very difficult because Aristotle, as it seems to me, has not solved it

well. For he ...[at one point] holds

that the projectile swiftly leaves the place in which it was, and nature, not

permitting a vacuum, rapidly sends air in behind to fill up the vacuum. The air

moved in this way impinges upon the projectile and impels it along. This is

repeated continually for a certain distance. ...[But] it seems to me that many

experiences show this method of proceeding to be valueless. ...

[For example, one among many that Buridan gives,] a lance having a

conical posterior as sharp as its anterior would be moved after projection just

as swiftly as it would be without a sharp conical posterior. But surely the air

following could not push on a sharp end in this way since the air would be

easily divided by the sharpness [whereas it could push on a blunt end, thus

moving the lance with the blunt end farther]. ...

Thus we can and ought to say that in the stone or other projectile

there is impressed something which is the motive force of that

projectile. This is evidently better than falling back on the statement that

the air would [continue to] move the projectile, for the air appears to resist.

...

[The projector] impresses a certain impetus or motive force into the

moving body, which impetus acts in the direction toward which the mover moved

the moving body, either up or down, or laterally or circularly. And by the

amount the motor moves that moving body more swiftly, by the same amount it

will impress in it a stronger impetus. It is by that impetus that the stone is

moved after the projector ceases to move. But that impetus is continually

decreased by the resisting air and by the gravity of the stone

which inclines it in a direction contrary to that in which the impetus

was naturally predisposed to move it. Thus the movement of the stone

continually becomes slower until the impetus is so diminished or corrupted that

the gravity of the stone wins out over it and moves the stone down to its

natural place.

Also, since the Bible does not state that appropriate [angelic]

intelligences move the celestial bodies, it could be said that it does not

appear necessary to posit intelligences of this kind. For it could [equally

well] be answered that God, when He created the world, moved each of the

celestial orbs as He pleased, and in moving them He impressed in them impetus

which moved them without His having to move them any more except by the method

of general influence whereby he concurs as a coagent in all things which take

place. Thus on the seventh day He rested from all

work which he had executed by committing to others the actions and the

passions in turn. And these impetuses which He impressed in the celestial

bodies were not decreased nor corrupted afterwards, because there was no

inclination of the celestial bodies for other movements. Nor was there

resistance which would be corruptive or repressive of that impetus.

-----------------------------------------------------------

Nicole Oresme, Le livre du ciel et du monde

[In response to Aristotle's and Ptolemy's argument] one may say that an

arrow shot straight into the air is [also] moved rapidly eastward with the air

through which it passes and with the whole mass of the bottommost [or

terrestrial] portions of the universe described above, the whole [earth and air

and arrow] being moved with a daily rotation. Therefore the arrow returns to

the spot on the earth from which it was shot. This appears possible by analogy:

if a man were on a ship moving rapidly eastward without his being aware of its

motion, and if he drew his hand rapidly downward, describing a straight line

against the mast of the ship, it would seem to him that his hand had only a

vertical motion; and the same argument shows why the arrow seems to us to go

straight up or down.

----------------------------------------------

René Descartes, Principles of Philosophy, 1644.

PART II

36 That God is the primary cause of motion; and that He always

maintains an equal quantity of it in the universe.

After having examined the nature of movement, we must consider its

cause, which is twofold: {we shall begin with} the universal and primary one,

which is the general cause of all the movements in the world; and then {we

shall consider} the particular ones, by which individual parts of matter

acquire movements which they did not previously have. As far as the general

{and first} cause is concerned, it seems obvious to me that this is none other

than God Himself, who, {being all-powerful} in the beginning created matter

with both movement and rest; and now maintains in the sum total of matter, by

His normal participation, the same quantity of motion and rest as He placed in

it at that time. For although motion is

only a mode of the matter which is moved, nevertheless there is a fixed and

determined quantity of it; which, as we can easily understand, can be always

the same in the universe as a whole even though there may at times be more or

less motion in certain of its individual parts. That is why we must think that when

one part of matter moves twice as fast as another twice as large, there is as

much motion in the smaller as in the larger; and that whenever the movement of

one part decreases, that of another increases exactly in proportion. We also

understand that it is one of God's perfections to be not only immutable in His

nature, but also immutable and completely constant in the way He acts. Thus,

with the exception of those changes which either manifest experience or divine

revelation renders certain, and which we either perceive or believe to occur

without any change on the part of the Creator; we must not suppose that there

are any others in His works, for fear of accusing Him of inconstancy. From this

it follows that it is completely consistent with reason for us to think that,

solely because God moved the parts of matter in diverse ways when He first

created them, and still maintains all this matter exactly as it was at its

creation, and subject to the same law as at that time; He also always maintains

in it an equal quantity of motion.

37 The first law of nature: that each thing, as far as is in its

power, always remains in the same state; and that consequently, when it is once

moved, it always continues to move.

Furthermore, from this same immutability of God, we can obtain

knowledge of the rules or laws of nature, which are the secondary and

particular causes of the diverse movements which we notice in individual

bodies. The first of these laws is that each thing, provided that it is simple

and, undivided, always remains in the same state as far as is in its power, and

never changes except by external causes. Thus, if some part of matter is

square, we are easily convinced that it will always remain square unless some

external intervention changes its shape. Similarly, if it is at rest, we do not

believe that it will ever begin to move unless driven to do so by some external

cause. Nor, if it is moving, is there any significant reason to think that it

will ever cease to move of its own accord and without some other thing which

impedes it. We must therefore conclude that whatever is moving always continues

to move as far as is in its power. However, because we inhabit the earth, which

is so constituted that all movements which occur near to it cease in a short while

(and frequently from causes which are concealed from our senses), we often

judged, from the beginning of our life, that those movements which thus ceased

for reasons unknown to us, did so of their own accord. Indeed, because

experience seems to have proved it to us on many occasions, we are still

inclined to believe that all movements cease by virtue of their own nature, or

that bodies have a tendency toward rest. Yet this is assuredly in complete

contradiction with the laws of nature; for rest is the opposite of movement,

and nothing moves by virtue of its own nature toward its opposite or its own

destruction.

38 Why bodies which have been thrown continue to move after they

leave the hand.

Indeed, daily experience of things which are thrown to a distance

confirms this {first} rule in every way. For there is no other reason why

things which have been thrown should continue to move for some time after they

have left the hand which threw them except that, {in accordance with the laws

of nature}, having once begun to move, they continue to do so until they are

slowed down by encounter with other bodies.

It is obvious, moreover, that they are always gradually slowed down,

either by the air itself or by some other fluid bodies through which they are

moving, and that, as a result, their movement cannot last for long. We can in

fact prove by our own sense of touch that the air resists the movement of other

bodies, if we shake an {open} fan vigorously. The flight of birds confirms the

same thing. Moreover, there is no other

fluid body {on the earth} which does not resist the movement of projectiles

even more manifestly than does the air.

39 The second law of nature: that all movement is, of itself, along

straight lines; and consequently, bodies which are moving in a circle always

tend to move away from the center of the circle which they are describing.

The second law of nature {which I observe} is: that each part of

matter, considered individually, tends to continue its movement only along

straight lines, and never along curved ones; even though many of these parts

are frequently forced to move aside because they encounter others in their

path, and even though, as stated before, in any movement, a circle of matter

which moves together is always in some way formed. This rule, like the

preceding one, results from the immutability and simplicity of the operation by

which God maintains movement in matter; for He only maintains it precisely as

it is at the very moment at which He is maintaining it, and not as it may perhaps

have been at some earlier time. Of

course, no movement is accomplished in an instant; yet it is obvious that every

moving body, at any given moment in the course of its movement, is inclined to

continue that movement in some direction in a straight line, and never in a

curved one.

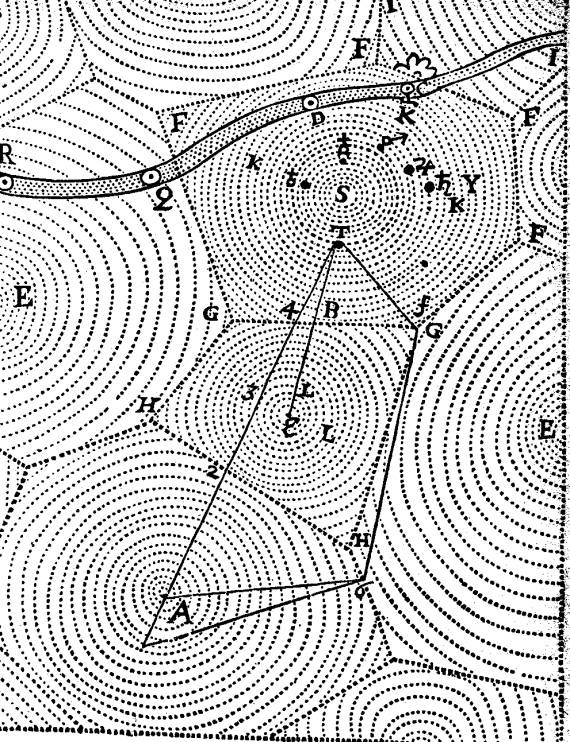

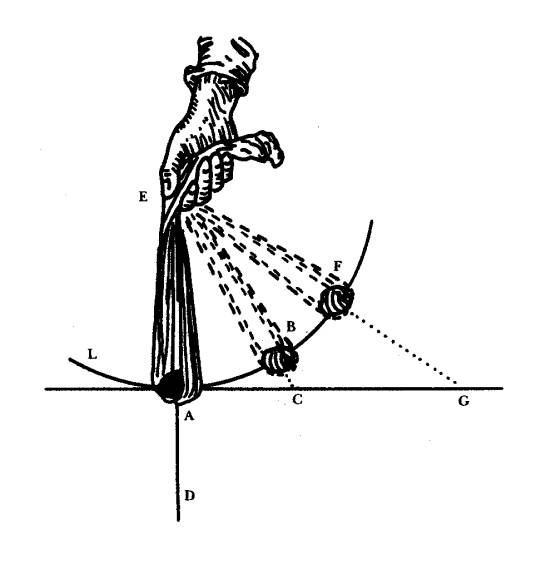

For example, when the stone A is rotated in the sling EA and describes

the circle ABF; at the instant at which it is at point A, it is inclined to

move along the tangent of the circle toward C. We cannot conceive that it is

inclined to any circular movement: for although it will have previously come

from L to A along a curved line, none of this circular movement can be

understood to remain in it when it is at point A. Moreover, this is confirmed by experience, because if the stone

then leaves the sling, it will continue to move, not toward B, but toward C.

From this it follows that any body which is moving in a circle constantly tends

to move [directly] away from the centre of the circle which it is describing.

Indeed, our hand can even feel this while we are turning the stone in the

sling, {for it pulls and stretches the rope in an attempt to move away from our

hand in a straight line}. This consideration {is of such importance, and} will

be so frequently used in what follows, that it must be very carefully noticed

here; I shall explain it more fully later.

40 The third law: that a body upon coming in contact with a stronger

one, loses none of its motion; but that, upon coming in contact with a weaker

one, it loses as much as it transfers to that weaker body.

This is the third law of nature: when a moving body meets another, if

it has less force to continue to move in a straight line than the other has to

resist it, it is turned aside in another direction, retaining its quantity of

motion and changing only the direction of that motion. If, however, it has more

force; it moves the other body with it, and loses as much of its motion as it

gives to that other. Thus, we know from experience that when any hard bodies

which have been set in motion strike an unyielding body, they do not on that

account cease moving, but are driven back in the opposite direction; on the

other hand, however, when they strike a yielding body to which they can easily

transfer all their motion, they immediately come to rest. All the individual

causes of the changes which occur in [the motion of] bodies are included under

this third law, or at least those causes which are physical; for I am not here

enquiring into what kind of power the minds of men or Angels may perhaps have

to move bodies; I am reserving that matter for a treatise on man.

64 That I do not accept or desire in Physics any other principles

than in Geometry or abstract Mathematics; because all the phenomena of nature

are explained thereby, and certain demonstrations concerning them can be given.

I shall not add anything here concerning figures, or the way in which

there also result, from their infinite diversity, innumerable diversities of

movement; because these things will be, of themselves, sufficiently obvious

when the occasion to discuss them arises. Furthermore, I am supposing that my

readers are already familiar with the rudiments of Geometry, or that they at

least have capacities adequate to the understanding of Mathematical demonstrations.

For I openly acknowledge that I know of no kind of material substance other

than that which can be divided, shaped, and moved in every possible way and

which Geometers call quantity and take to be the object of their

demonstrations. And [I also acknowledge] that there is absolutely nothing to

investigate about this substance except those divisions, shapes, and movements;

and that nothing concerning these can be accepted as true unless it is deduced

from common notions, whose truth we cannot doubt, with such certainty that it

must be considered as a Mathematical demonstration. And because all Natural

Phenomena can thus be explained, as will appear in what follows; I think that

no other principles of Physics should be accepted, or even desired.

Vortex theory