Histograms, Measurement, and Uncertainty

You've

probably run into this symbol before: +/-. You see it in the news when

political polls are being discussed, or in science textbooks. You know it has

something to do with "error". But what does it really mean?

Part

of the confusion is that it seems to mean different things at different times.

Let's say you're in science class. You fill a graduated cylinder with water up

to the 50 mL mark. At the top of the beaker it tells you that the beaker is

accurate to +/- 0.5 mL. You take that to mean that

the water in the beaker could actually be as low as 49.5 mL or as high as 50.5

mL, but definitely not outside that range.

Now

let's say you're reading a news report. A bunch of people were asked to rate

how well a political leader is doing, on a ten point score. The news reports

that the average was 5.5 +/- 0.2. So does that mean that all the people polled

picked a score between 5.3 and 5.7? That doesn't seem possible; you know that

some people hate this political leader and others love her.

To

sort this out, we need to start by talking about uncertainty. Some people call

it "error", and mean the same thing, but "uncertainty" is a little more

accurate. So what is it? Well, any time you (or anyone else) measures something,

whether it be mass, length, calorie intake, heart rate, public opinion, average

happiness, or anything else, you're limited in how precisely you can know your

result. Your ruler doesn't have ticks all the way down to nanometres, or each

hamburger has a slightly different number of calories, or you can only poll

1000 people and extrapolate out to 100,000,000 people. All measurements are

limited. So we need a way to express how well we actually know the result of

our measurement, which is where uncertainty and the +/-

symbol come in.

As

an aside, since all measurements are limited, you should always be a little

suspicious when you read about a measurement and the uncertainty isn't mentioned.

Uncertainty is always there; if it's not mentioned the person

writing the article either didn't know what it was or deliberately left it

out--in either case it's a red flag that there could be a problem with the

article.

You

may have noticed that I'm being a little vague about uncertainty. This is

actually on purpose. It turns out that there are a bunch of different ways of

mathematically expressing "how well we actually know the result of our

measurement." It's not that some are right and some are wrong, but that

different measures make sense in different contexts. The graduated cylinder

example and the political poll example are using two different measures of

uncertainty because each is using a measure that makes sense for that context.

Before

we can really talk about that, though, we need a more concrete idea about what

uncertainty is. So now I'm going to introduce a particularly powerful tool for

understanding measurement and uncertainty: the histogram.

Histograms

are a type of graph, though they're a little more abstract than the type of

graph you may be used to. A histogram takes a bunch of individual measurements

and plots the number of times a given measurement occurs against the value of

that measurement. It really helps to have a concrete example here, so let's go

through one.

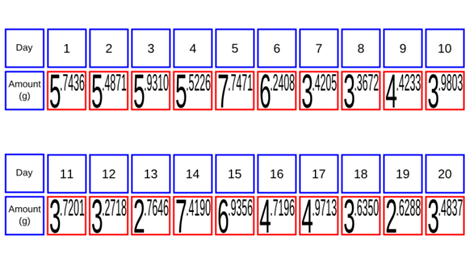

Suppose

you have a pet hamster. You want to know, "How much food does my hamster eat in

a day?" So you start weighing its food each day. You do this for 20 days, which

gives you the following table:

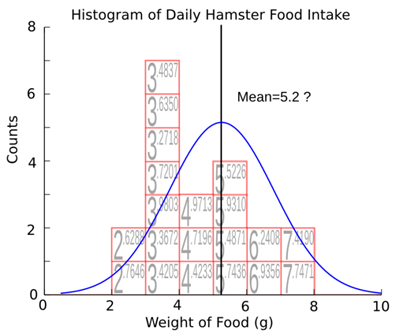

You'll

notice that the amount moves around a bit; the highest amount is more

than 7

grams, while the lowest is less than 3. So while you can add them all

up and

average them to get 4.77 grams per day, you also want to somehow

communicate

what the range around that is. To do that, we'll re-sort each day's

measurement. First we create a plot with "Weight of Food (g)" on the

x-axis and "Counts" on the y-axis. Then we stack each day's measurement

on our plot: all

the measurements between 2 and 3 get stacked in the space between 2 and

3 on

the x-axis, and likewise for measurements between 3 and 4, between 4

and 5,

etc. Here's an animation of what I mean:

As

an aside, we call these ranges "bins". They don't have to be integer numbers; I

could have stacked all the measurements between 2.0 and 2.5 in a separate pile

from the ones between 2.5 and 3.0. Picking good bins is an art unto itself; I

won't say much about it here except that the only overarching goal in picking

bins is to get a useful histogram. For this example, integer bins work well.

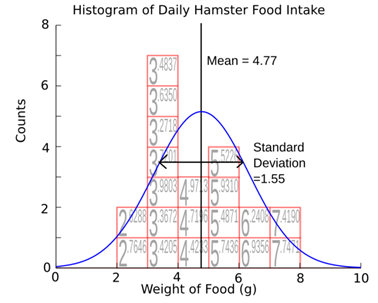

Now

I have a plot of the number of times I got a certain measurement vs what that

measurement was. As you can see, it has a hill-like structure: most of the

measurements were in the 3-4, 4-5, and 5-6 bins, with a few in the surrounding

ones and none smaller than 2 g or larger than 8 g.

Already

this plot helps us to visualize our data, but we can do more. In the next plot

I'm going to add something we call a distribution. This is a curve that

represents the ideal, what our histogram "should" look like. You can see that

it's smooth, unlike our actual histogram, and shaped somewhat like a

bell--which is where the term "bell curve" comes from.

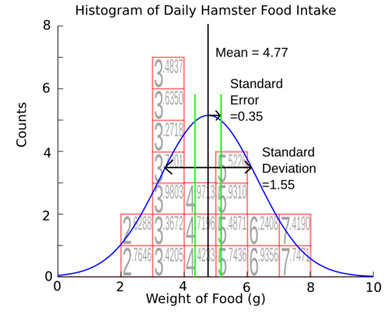

There's

two properties of this distribution that you might be familiar with. The first

is the mean. You might know it better as the average--we use the term "mean"

because our everyday usage of "average" can actually refer to a few different

things. It's the centre of the peak, and also what you get if you add up all of

your measurements and divide by the number of measurements you made. The second

quantity that you may have encountered before is something called the standard

deviation. This is a measure of how wide the peak is. You can get if from your

data with formula:

![]()

This

formula tells you that the standard deviation is the sum (![]() of

the difference between each measurement and the mean

of

the difference between each measurement and the mean ![]() squared,

divided by the number of measurements, all square rooted.

squared,

divided by the number of measurements, all square rooted.

That

seems complicated, but the key point here is that it represents how wide your

distribution is, or equivalently how spread out your measurements were. For our

hamster food, the mean is 4.77 grams, and the standard deviation was 1.34

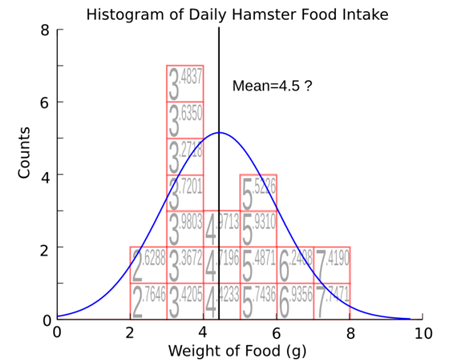

grams. There is another thing we might like to know. And that is, how certain

are we that our distribution is the right one? A distribution with a mean of

4.77 and a standard deviation of 1.34 was the one that best fit the histogram

we have, but we can move the distribution to the left, like this,

or

to the right, like this,

and

looks like it fits our histogram almost as well. This quantity, how far we can

move our distribution before it stops fitting our histogram, is called the

standard error. Conceptually, it is how certain we are that the average we got

from our data is the right average. Mathematically, it's given by the formula

![]()

If

you look at the formula, you'll notice two things. First, the standard error is

proportional to the standard deviation. That means that the more spread out the

data is, the bigger the range we need to put on our average is. This makes

sense: if every day our hamster had eaten exactly 4.5 grams of food, we'd be

pretty confident that the daily average was very close to 4.5--certainly not

4.8, say. On the other extreme, if every day the hamster had eaten a widely

different amount--some days 0.5 grams, other days 15 grams, we wouldn't be very

confident in the average we got after only 20 days. We might want to watch the

hamster for longer to make sure we were getting the right average.

This

brings us to the second part of the equation for standard error. The ![]() in the bottom means that the standard error

goes down as the number of measurements goes up. Intuitively, this makes sense:

the more measurements we make, the more confident we are that our average is

true. To further flesh out these three important quantities (mean, standard

deviation, and standard error) we can look at histograms for our hamster data

as we take more and more of it. We've already looked at the data for 20 days.

in the bottom means that the standard error

goes down as the number of measurements goes up. Intuitively, this makes sense:

the more measurements we make, the more confident we are that our average is

true. To further flesh out these three important quantities (mean, standard

deviation, and standard error) we can look at histograms for our hamster data

as we take more and more of it. We've already looked at the data for 20 days.

You

can see I've added some green lines to indicate where the standard error is.

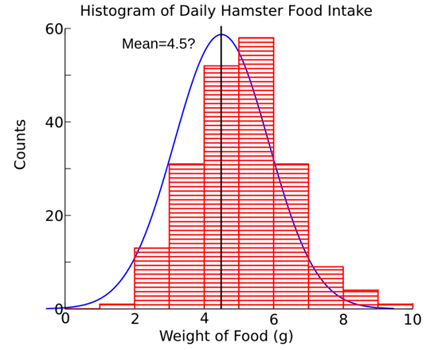

Now we follow our hamster for 200 days:

You'll

notice we have a lot more counts here; that's fine, we can still overlay our

distribution. What happened to our three quantities? The mean moved a bit--we

expect this to happen. After all, if the mean never moved when we added more

data, it would mean that our original estimate was exactly right, in which case

there wouldn't be any uncertainty. The standard deviation moved some too. It

happened to have gotten smaller, but this won't always be true. The standard

deviation remains approximately the same, but tends to move around fairly

randomly as you add more and more data. Looking at the standard error, you can

see it got much smaller. Another way of seeing this is to notice that the

bell-shape of our histogram is much more defined. What this means is that the

uncertainty in the average is much less, because we couldn't move our

distribution very far either way before it was a noticeably worse fit to our

data. For example, if we tried to move our distribution to the left like we did

above, we get:

Unlike

our 200 day example, this is clearly a much worse fit than a mean of 5.05.

Now

we follow our hamster for 20,000 days. Okay, hamsters don't live that long, but

we can imagine that we've gotten together with all our friends to compile the

results of a hundred hamsters for 200 days each.

The

same trend happened here as did before: the mean and the standard deviation

moved a little, and the standard error got a lot smaller--so small that the

green lines have disappeared. You'll notice that the histogram is now

practically an exact fit to the distribution, which means the distance we could

move the distribution in either direction is extremely small.

Now

we're in a position to take another look at what uncertainty is. Let's ask two

different questions. 1. How much food on average does a hamster in my

neighbourhood eat each day? 2. How much food will my hamster eat tomorrow?

The

best answer I can give to question 1 is 4.979 +/- 0.009 grams. The best answer

I can give to question 2 is 5.0 +/- 1 gram. Let's go over the difference

between these two answers. In the first case, I want to know how confident I am

in my mean. In this case I use the standard error as my uncertainty, because

the standard error represents the amount I could move my distribution and still

fit the histogram; it's the uncertainty in the mean. In the second case, I want

to know what I can expect on a typical day. Here I use the standard deviation

as my uncertainty, because the standard deviation represents how much a

hamster's food intake might vary from day to day.

Now

let's go back to the examples we started with. A graduated cylinder says "+/-

0.5 mL" on it. What this means is that the company that makes the graduated

cylinders took a whole bunch of the cylinders off the line at the factory and

used each them to measure, say 100 mL of water, at various temperatures

conditions. They read off the measurements and built a histogram like we did

above, and found that the standard deviation of the measurements was 0.5 mL. They report the standard deviation because what you

want to know is how far away from the true value your individual graduated

cylinder is likely to be.

The

pollster who reports the result of a ten-point approval scale is using the

standard error for their uncertainty. In that case, you're not too concerned

with how likely it is that your neighbour's opinion is far from that mean.

Instead you want to know how accurate the mean itself is; in other words, how

much the poll would change if it was extended to the entire country. Since the

standard error is a measure of uncertainty in the mean, it's a good choice to

use here.

Keep

in mind the uncertainty represents our knowledge, as the name suggests. It's

possible, in the graduated cylinder example, that you

happen to have a particularly well calibrated cylinder, in which case your

readings are actually closer to the true volume than 0.5 mL; but since you

don't know this, your uncertainty is still 0.5 mL.

It's even possible to change the uncertainty: you could calibrate the cylinder yourself,

using some other, more precise way of measuring volume. You could build a whole

table this way, so that you knew that when the graduated cylinder read 50 mL,

it actually held 50.35 +/- 0.05 mL. If you did that,

the uncertainty on the cylinder would be less, because you would know more

about it, even though the graduated cylinder didn't actually change.

There

was a lot in this article, so letís go over the important points.

-

Uncertainty is always present when

you measure something, because no measurement tool is perfect. You should

expect measurements you read about to report uncertainty, and be suspicious of

those that don't. You should also report uncertainty in your own measurements

if you want other people to have confidence in them.

-

There are a number of different ways

of calculating uncertainty. Which way you should use depends largely on the

context you're using it in.

-

Histograms are useful tools for

visualizing and understanding data. They consist of a graph that plots how

often you got a certain measurement against the value of that measurement.

-

Three important quantities you can

get out of a set of data are the mean, the standard deviation, and the standard

error. The mean is the average. The standard deviation tells you how spread out

the data is. The standard error tells you how confident you are in the mean you

found. You might use either the standard deviation or the standard error as

your uncertainty, depending on the situation. The standard deviation is

appropriate as the uncertainty on a single measurement. The standard error is

appropriate as the uncertainty on the average of a number of measurements.

Hopefully

now you have an idea of what the number after the +/- sign means. Now go use

it!

Futher

reading and resources:

Data Reduction and Error Analysis in the Physical

Sciences, by Bevington

and Robinson (McGraw-Hill 2003) is a bit high level, but the first few chapters

give an excellent and concise introduction to some of the topics discussed

here. The wikipedia articles on mean, standard deviation, standard error, and normal distribution are all good places to start.

To

actually do the calculations I did to generate all the plots shown here, I

used Octave, which is a free version of Matlab,

and gnuplot,

which in addition to plotting also has a variety of fitting options. To make

the graphs more informative I used Inkscape, a free drawing tool for Linux

and Mac.

copyright: Physics and Astronomy Outreach Program at the University of British Columbia

(Eric Mills 2013-08-21)